Yesterday involved a bike ride out to Azabu Juban to collect a visa-stamped passport from an embassy.

The process of applying for a visa and then arriving at the embassy to pick it up often provides the first “Oh, I’m going to…” moments – when it first sinks in that in a month or so you’ll be living, working and documenting that culture and its peoples. The practical issues hit home – of researching in a new language, trying to figure out what it takes to get the job done all with a sufficient cultural sensitivity, naturally.

The act of making a visa application implies that other plans are well progressed – the research brief is far enough along, project dates are fixed, and that conversations with collaboration partners are sufficiently progressed. In a sense the visit is a time marker, the beginning of the count down clock. (I can’t think of anyone who applies for visas for the fun of it though somebody out there probably does). The embassy visit is certainly not the first point of contact with a culture – a considerable amount of communication will have already taken place with local guides, organisations and the background research will be well underway. There is nothing like being in the richness of a physical space to bring it home. Online? By the time we develop comparatively rich digital environments that could evoke the same feelings we will have found new ways to look at and appreciate our physical surroundings.

Embassies are mostly run according to home culture norms: separate kiosks for men and women; television tuned to local entertainment channels (in this instance a gentleman is walking around a restaurant holding a microphone and singing – something that is no-doubt a pleasant enough way to pass the time); paintings of leaders and spiritual leaders side by side; the application process itself (for me an official invitation stamped by the Ministry of Lmnop), and finally there is the language that is spoken and, literally, the language of the writing on the wall.

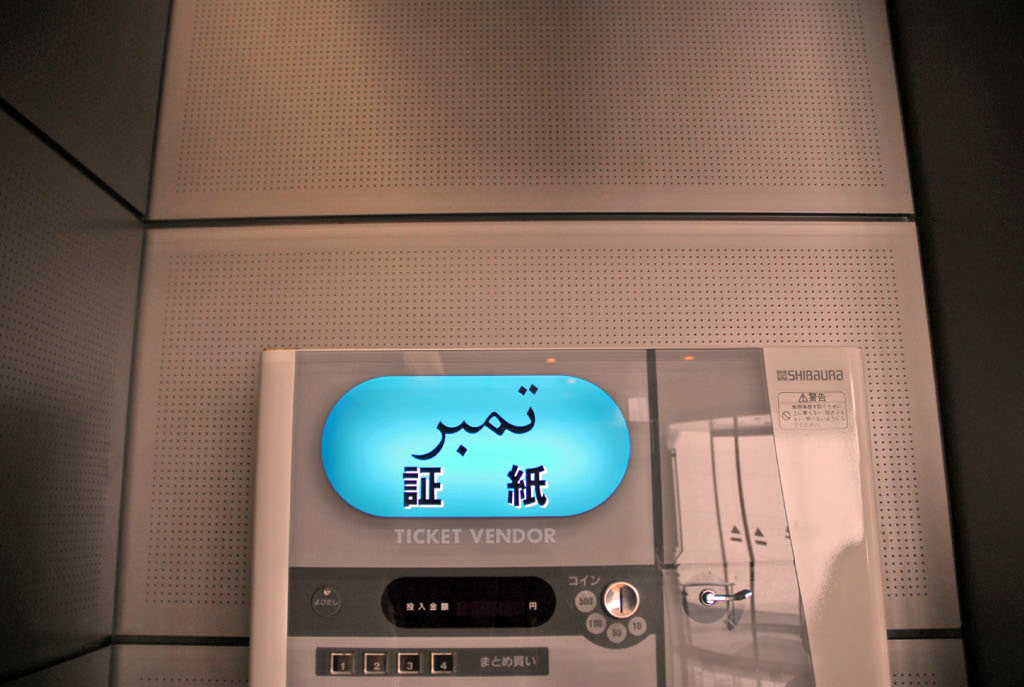

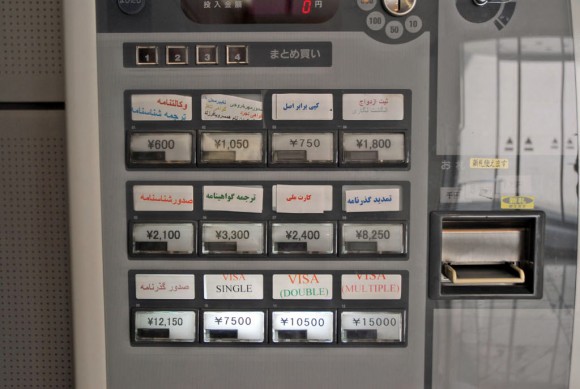

Little touches of home culture make through the kiosk glass: the manner in which overly zealous applicants are rebuffed; the degree to which personal time and space is acknowledged and the manner in which this acknowledgement is appreciated; and an honest desire to share the best of one’s culture. And then there’s the cross-cultural – a visa stamp vending machine in Arabic and Japanese.

I must admit to being a little surprised that taking photos was allowed in this consulate office (though I did restrict the lens to the direction of inanimate objects). No smoking and no mobile phones certainly, but no no-cameras. What does your embassy not allow you to do within its walls? What does it say about your culture that it has these rules? How does it reflect on the way your country conducts itself abroad? Or the perception of your country in these foreign lands?

My home country embassy confiscates cameras at its entrance and returns them on your way out.

And this morning’s embassy? You’ll know when I get there.